Every Valentine’s Day, we envision the joy of receiving just one traditional, lacey confection pulsating with sugary sentiment and the familiar iconography of love: Cupid’s bow and arrows, and hearts, often aflame, accompanied by tender verse conveyed in delicate calligraphy. But that is only part of the story of the valentine. As the market for sentimental cards expanded, another variety of valentine grew popular. Known as the “vinegar valentine,” or “penny dreadful,” this form of satirical Victorian missive has a long history.

Until the popular distraction of the Christmas card, Saint Valentine’s Day was certainly the most important holiday and a major season for business in the United States and England. Valentines were enjoyed by nearly everyone, and competition was strong among those early British lace-paper makers to create the most beautiful and ingenious designs to captivate the public. Perfumed sachets, fans trimmed with marabou feathers, and tiny reducing mirrors, in which the entire face of the beloved could be seen, were but a few of the embellished gems. For the non-romantics, it was an equally major holiday to mock and humiliate. Manufacturers were emboldened to create the most alarming original designs, providing personal character assassination, hurtful body shaming, and a great deal of double entendre or overt vulgarity.

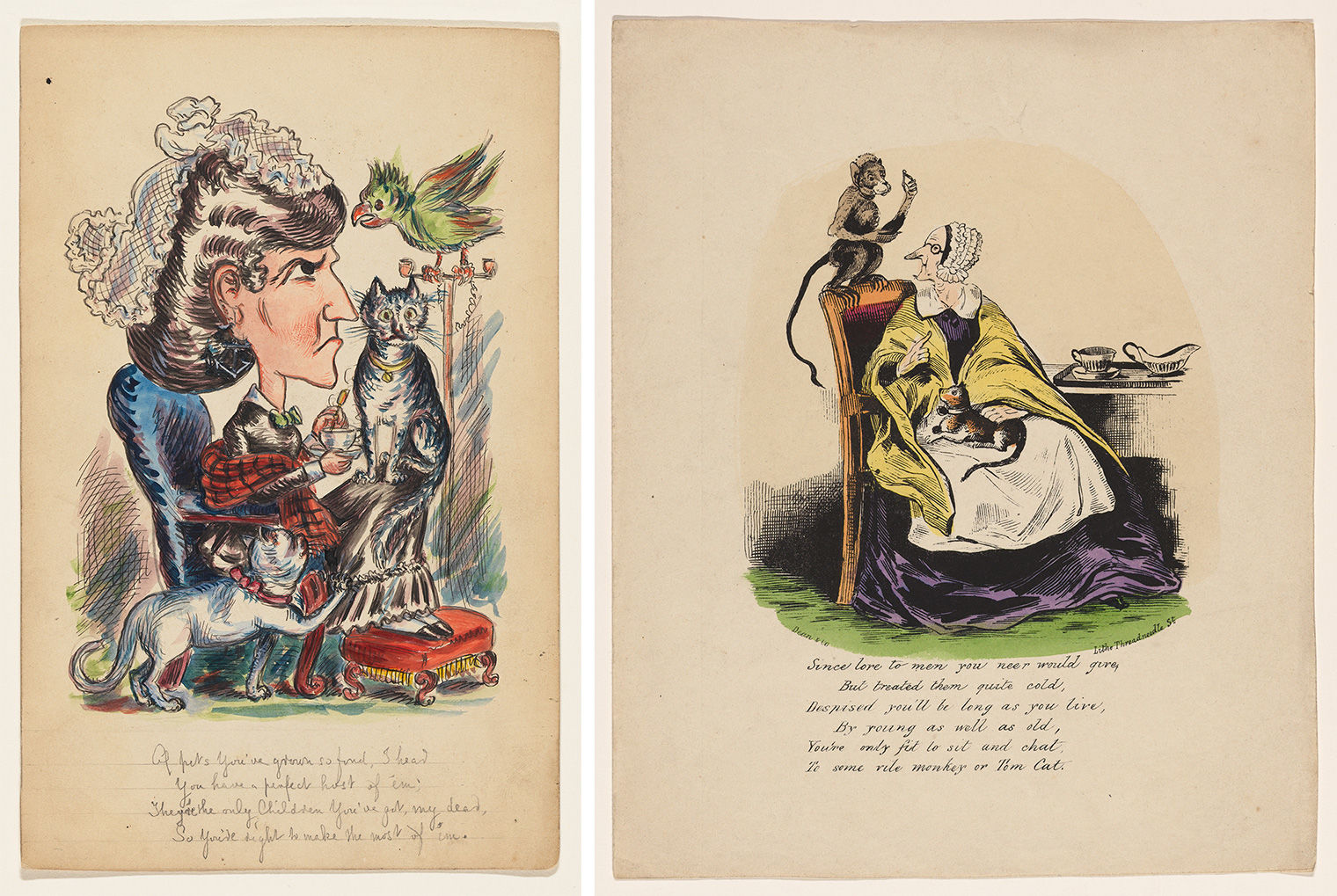

Left: British, 19th century. Comic Valentine (Despising Valentine), 1820. Hand colored engraving, 9 1/2 × 7 7/8 in. (24 × 20 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.403). Right: British, 19th century. Comic Valentine original illustration: The Flirt, ca. 1860. Black ink, hand colored with realistic watercolor, 5 7/8 × 4 1/2 in. (15 × 11.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Ref.ComicValentine.2)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art now holds numerous boxes filled with examples of these pointed missives alongside hundreds of their sentimental counterparts. Benefiting from a gift from devoted collector Jean Riddell in 1981, the Museum holds a large collection ranging from rare eighteenth-century hand-cut items through the valentine’s development during the nineteenth century. The collection reflects the finest examples of every type.

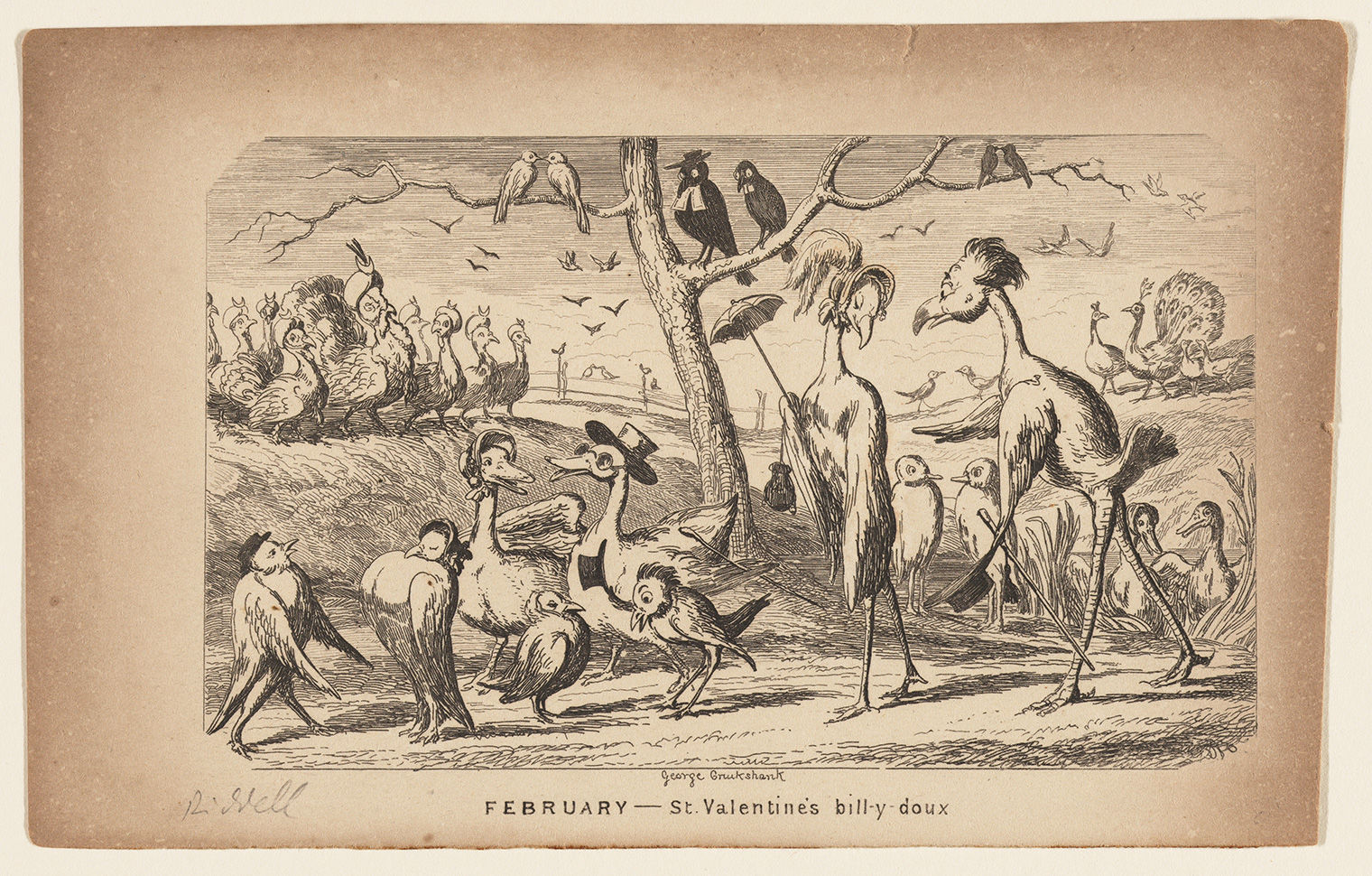

The earliest comic valentines are British. They evolved from the eighteenth-century caricature and satirical works of famous satirists like William Hogarth, James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, and George Cruikshank who focused on contemporary political and social themes and mocked wealth, vice, and celebrity. Exaggerated imagery and ironic symbolism were designed to raise awareness of societal failures and fears and to prompt change. While these popular critiques were aimed at embarrassing and humiliating their subjects, they were also a form of carefree, if occasionally hurtful, entertainment.

Many British publications in the early nineteenth century, such as Figaro and Punch, devoted entire issues to caricaturing prominent politicians, publicly denouncing their policies or scandals with ribald poetry. In James Gillray’s Pillars of the Constitution (1809), two inebriated statesmen, identified as Sheridan and the Duke of Norfolk, exit a pub looking embarrassingly disheveled.

James Gillray (British, 1756-1815). Publisher: Hannah Humphrey (British, ca. 1745-1819). Pillars of the Constitution, February 1, 1809. Hand-colored etching, 13 3/4 x 9 7/8 in. (34.8 x 24.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917 (17.3.888-80)

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, comic flirtations, absurd fashion trends, and the intrigues and dangers of love increasingly served as daily fodder for British caricaturists in addition to political satire. Some of these political artists, especially the Cruikshank family—Isaac, Robert, and George—were simultaneously active in the romantic valentine trade, so we can see a distinct segue, and symbiotic relationship, between eighteenth-century satire and early nineteenth-century valentines.

George Cruikshank (British, 1792-1878). Comic Valentine (St. Valentine bill-y doux), 1841. Lithograph, 4 × 6 1/2 in. (10 × 16.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.367)

Generally sent anonymously, these valentines were solely intended to insult, attack, humiliate, or otherwise torment their recipient. Scholars recognize them as an important social chronicle, and study them as fascinating documents of contemporary life. Early nineteenth-century ones were often expensively engraved on fine paper, and later penny ones on cheap pulp, but it is thought that both were often discarded or destroyed due to their painful content. They were never considered worthy of saving as an interesting historical note, as scholars do today.

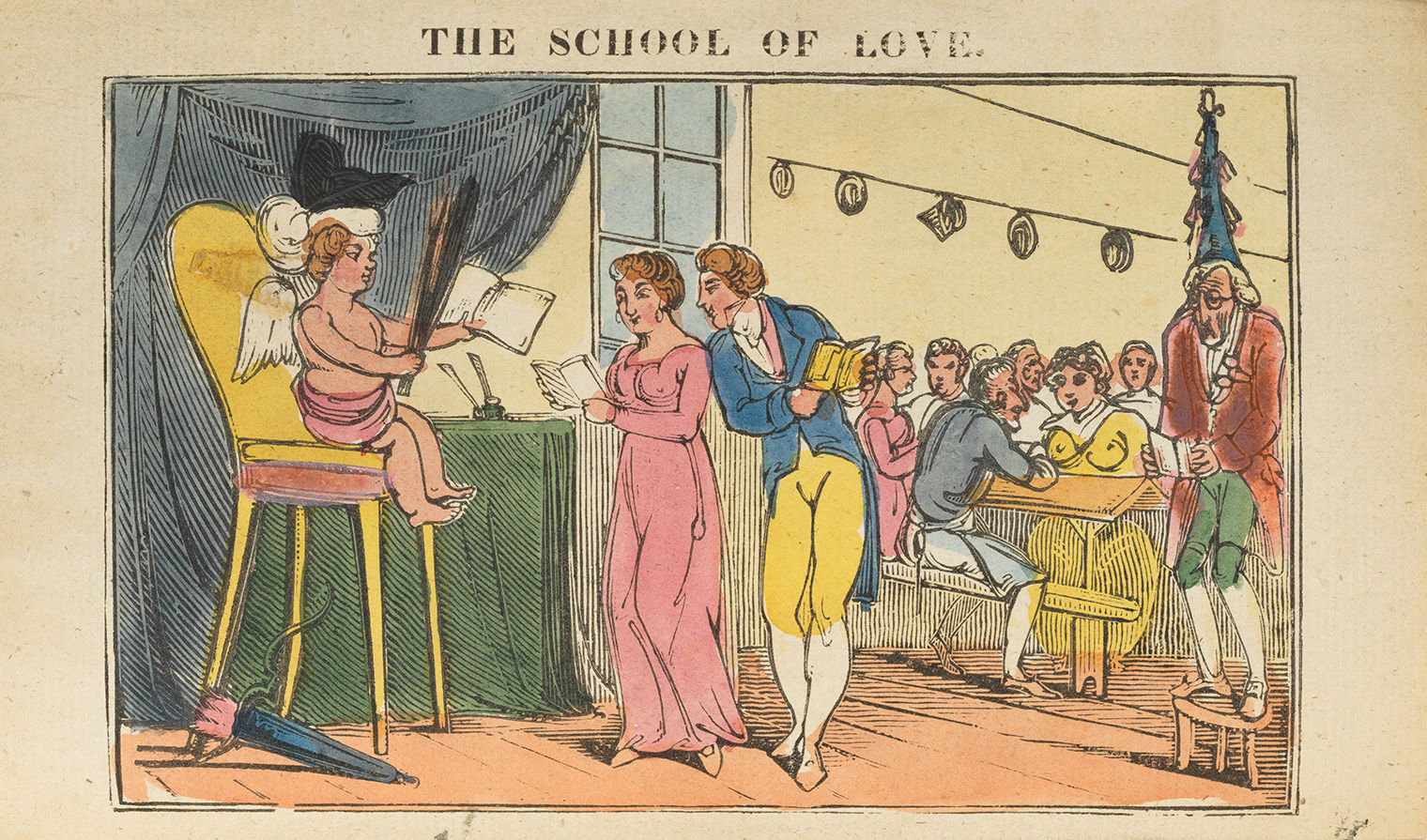

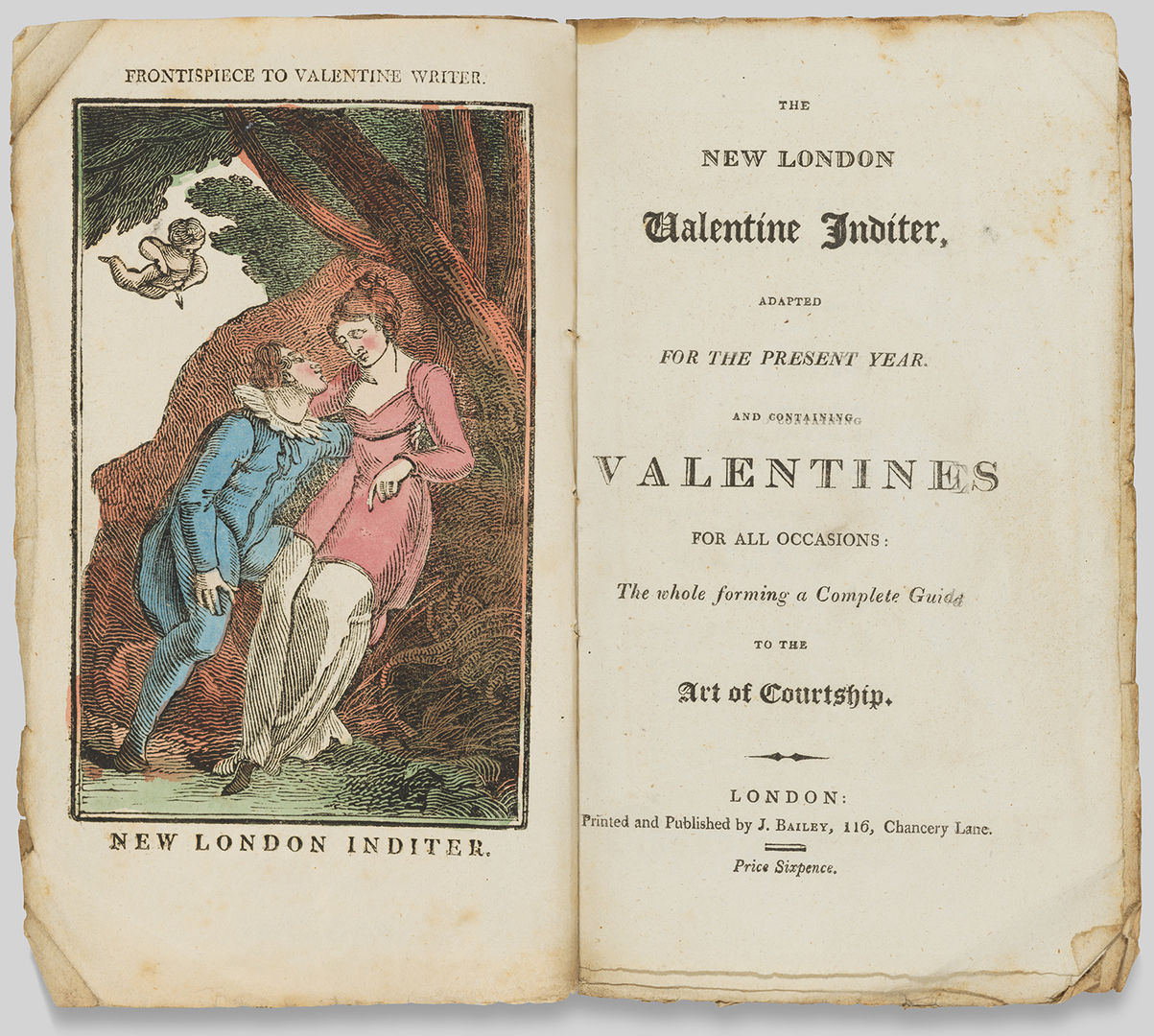

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, publishers were eager to capitalize on the profits of the industry and meet customer demand. While shops provided pre-made valentines, their sentiments were not always personal, so the “Valentine Writer” emerged as a handy, essential resource for the tongue-tied. These chapbooks were designed to serve a wide range of purposes and audiences, from the members of high society to bawdy tradesmen and sailors. Poems could be selected according to class and position: erudite and literary, with acrostics and references to the language of flowers, or for the “trades,” meaning anyone from a bricklayer to a baker. Often it would include a Message, for the sender, and the Answer, for the recipient. These sample poems and rhymes could then be written on a valentine. If the sender was illiterate, a shopkeeper could add the lines.

George Cruikshank (British, 1792-1878). Publisher: Mrs. Perks (British). Printer: D. S. Maurice (British). The School of Love; or, Original and Comic Valentine Writer, for Trades, Professions, &c., 1814. Wood engraving, hand colored, 7 1/2 x 4 5/8 in. (19 x 11.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.40)

Illustrations were often included as the frontispiece to a writer, which could easily be removed and sent as a valentine; others were produced and marketed separately to appeal to the increasingly popular trade. They were engraved on watermarked laid paper, and hand water-colored. Before long, lithographed or wood-engraved mock valentines complemented the sentimental ones that were sold early in the nineteenth century.

Publisher: J. Bailey (British). The New London Valentine Inditer Adapted or the Present Year, and Containing Valentines for All Occasions, 1808-24. Wood engraving, hand-colored, 7 1/2 x 4 1/2 in. (18.9 x 11.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.2)

As early as the 1840s companies in New York City, such as Robert Elton and Thomas Strong, were selling “a few” comical valentines, including their own “writers,” which were made smaller than the English versions and conveniently pocket-sized for ready reference. By the 1850s, thousands of comic valentines were being sold. The McLoughlin Brothers even specialized in them, and surprisingly, these caustic valentines became enormously popular, lampooning trades and professions, racial and ethnic groups, fashion trends and body flaws, while reveling in ribald innuendo. The role of the comic valentine became an opportunity to privately mock and distort marital strife and gender roles, to undermine women’s power, and even to justify the movement of women beyond their traditional “spheres.”

A consistently popular theme was the “old maid.” Interpreted as old and ugly, befriended only by pets or left waiting at the church, she is often depicted uncharitably. It is apparent they would not be sent to one’s beloved! Other equally vicious versions might attack men, notably their physical manliness, unsavory character, or poverty. These might be sent as anonymous insults from hard-hearted associates, or in jest to friends who might enjoy the joke.

Left: N. Clayton (British, 19th century). Original illustration for a comic Valentine: Old Maid with parrot and cat, ca. 1860. Hand-colored (watercolor) ink drawing on heavy stock, with poetry written in graphite script, 8 1/2 × 5 1/2 in. (21.5 × 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Ref.Clayton.1). Right: British, 19th century. Publisher: Dean and Co. (British). Comic Valentine (Old Maid), ca. 1860. Hand colored lithograph, watercolor, 5 3/4 x 4 in. (14.5 x 10 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.368)

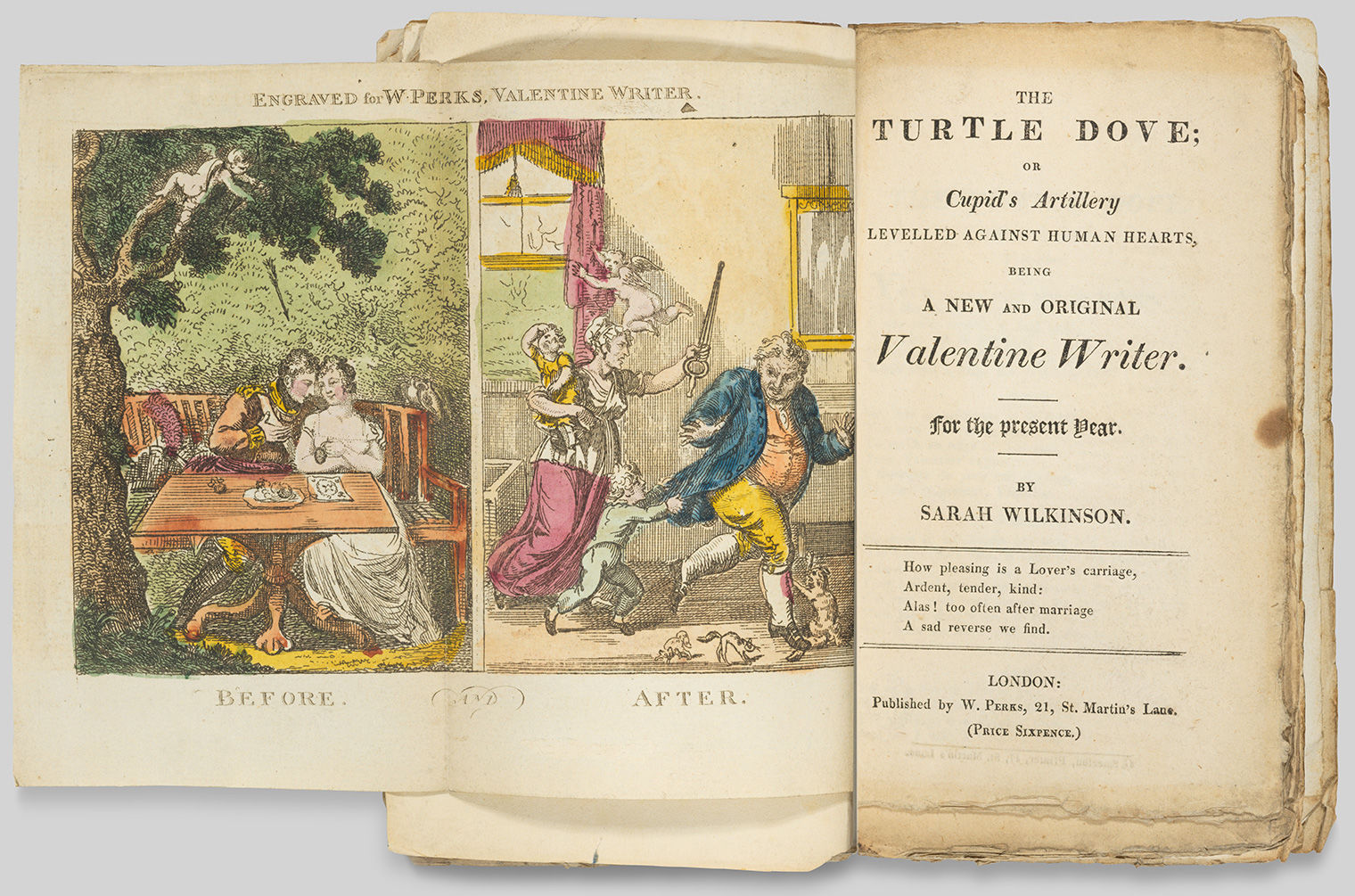

Another popular theme was “before and after,” showing the perils and often the realities of marriage. In this version, the amorous couple is seen on the left, with Cupid aiming his arrows. On the right, years later, Cupid is trying to escape out the window while the overworked wife, babe in arms, chases the fattened husband with her umbrella. One must wonder at the reaction if this page had been removed and sent as a humiliating valentine. Published by Perks, a major producer of these “writers,” this one was written by Sarah Wilkinson, a famous female author of Gothic fiction, with her own very sad story. [1] As a single mother with a deadly illness, she struggled greatly, and her writing of novels and poems helped to provide meager survival for her family.

Illustrator: Isaac Cruikshank (British [born Scotland], 1764-1811). Author: Sarah Scudgell Wilkinson (British, 1779-1831). Publisher: W. Perks (British). The Turtle Dove or Cupid's Artillery, etc., Being a New and Original Valentine Writer for the Present Year, before 1811. Etching, hand colored, 7 1/4 x 4 1/2 in. (18.4 x 11.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.39)

The color red has long been employed by women to fascinating effect, and in the 1830s, the significance of the red petticoat, specifically, ranged from romance and social status to rebellion, protest, and even to literary heroines. The practical flannel petticoat was a working girls’ staple to keep her legs warm, while wealthy women had them made of silk or cashmere, adding a vibrant flash of color and style to their ensemble. Red became a popular, eye-catching fashion choice, used by women to express passion, courage, and even emotional survival. This historic symbolism was not lost on the colorist of the valentines we see here, and we can read his subliminal messages. These women seem self-assured and unbothered by the satirists’ efforts to demean. The crinoline, on the other hand, was difficult to maneuver, and became a popular subject for attack.

Left: British, 19th century. Comic Valentine (Crinoline), ca. 1840. Hand colored wood engraving, 9 1/2 × 7 1/8 in. (24 × 18 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.366). Right: William Henry Harrison (British, ca. 1795-1878). Comic Valentine (Crinoline), ca. 1840. Hand colored wood engraving with lithograph, 6 3/4 × 8 3/4 in. (17 × 22 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.385)

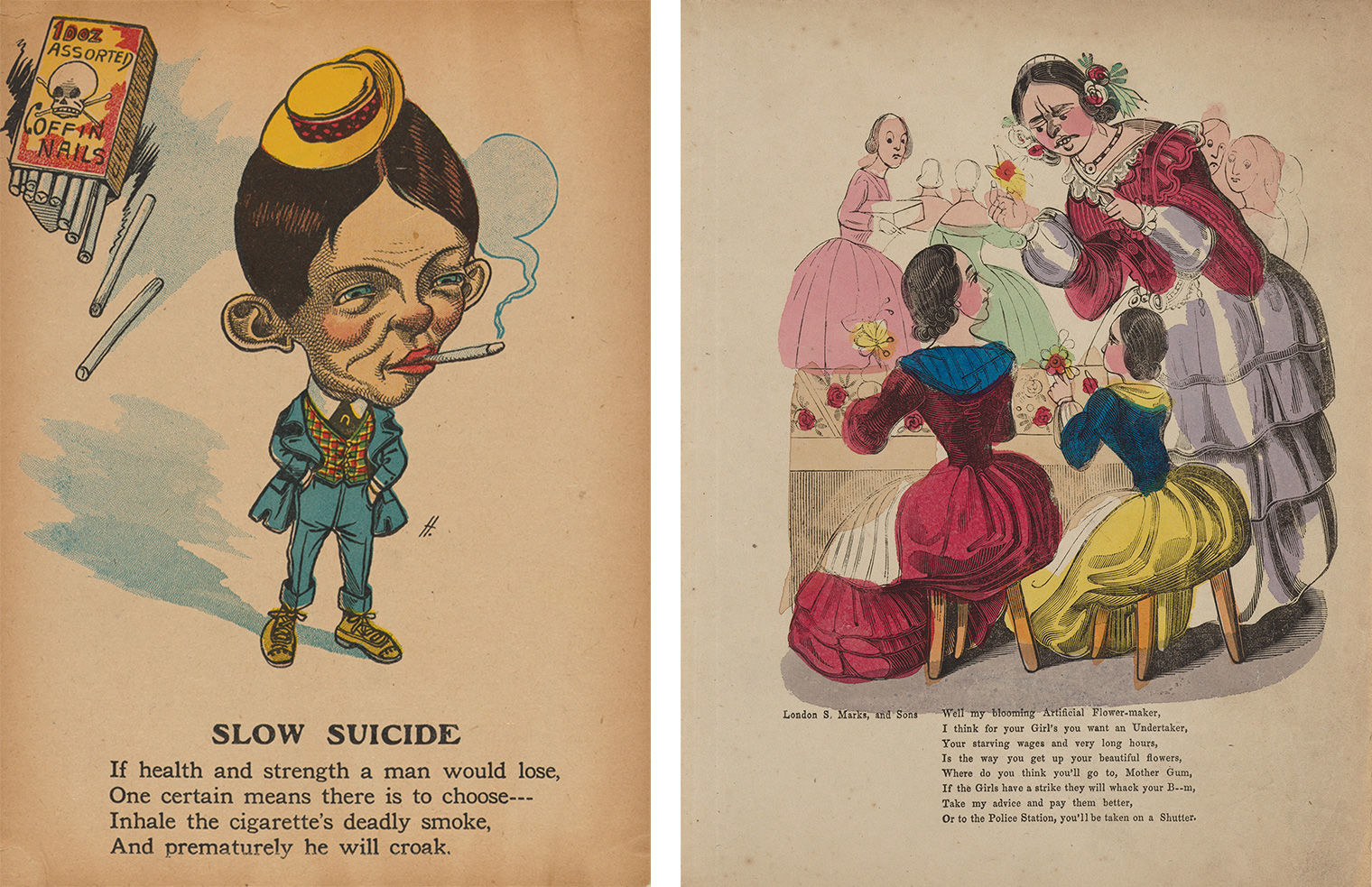

These images, which were parodies of everyone, sometimes sought to effect changes in habits and lifestyle, with accents on suffrage, exaggerated fashion, smoking, alcoholism, obesity, and the hard lives of women and workers. After the initial laughter, however, some may have taken the subliminal messages to heart.

Left: Charles J. Howard (American, 19th century). Publisher: McLoughlin Brothers (American, 1859-1920). Comic Valentine (slow suicide, anti-smoking), ca. 1880. Hand-colored wood engraving, 9 7/8 × 7 1/2 in. (25 × 19 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Jefferson R. Burdick Fund, 1976 (1976.630.1.44). Right: Unknown Artist, London S. Marks and Sons. Comic Valentine (working conditions - strike), ca.1840. Hand colored lithograph, 8 7/8 × 6 3/4 in. (22.5 × 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.388)

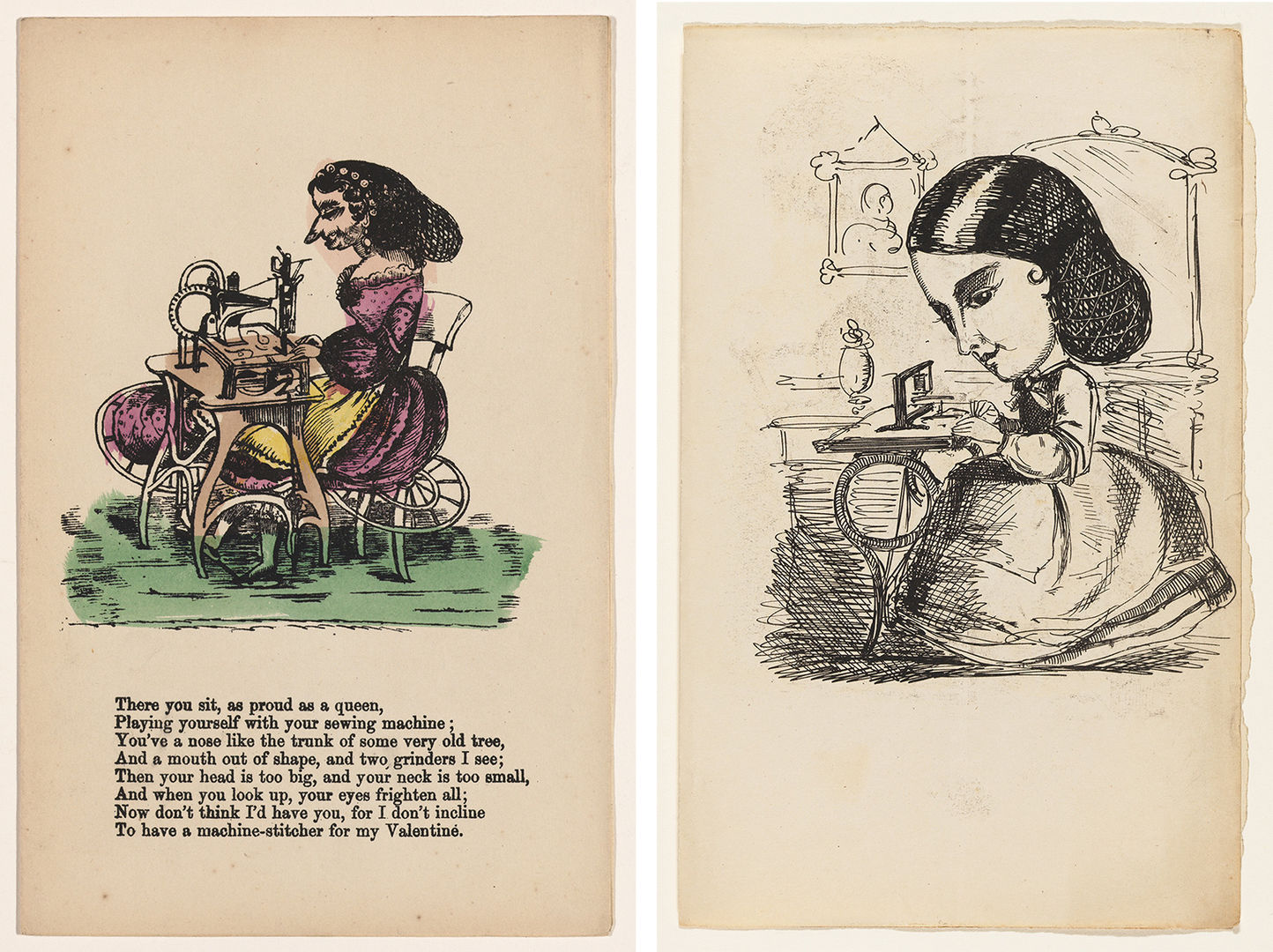

Original comic and caricature designs were eagerly received by manufacturers and reveal an interesting view of their business strategy, the process, and the mind of the artist, always trying to succeed with more outlandish designs. Often the same concept is reflected in the differing work of several companies. Below, women at their sewing machines, one is a hand-colored wood engraving, the other an original ink drawing.

Left: British, 19th century. Comic Valentine (woman at sewing machine), ca. 1850. Hand colored wood engraving, 7 1/2 × 4 3/8 in. (19 × 11 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.479). Right: British, 19th century. Comic Valentine original illustration: Sewing Machine, ca. 1860. Ink, 7 7/8 × 5 in. (20 × 12.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Ref.ComicValentine.1)

Leigh Eric Schmidt brilliantly described the popular American comic valentine history and how the market for such emotional expression brought them to prominence: “As coarse as the sentimental ones were refined, mock valentines were caricatures, grotesques. They emerged as the carnivalesque underbelly of a holiday prone to mawkish sentimentality. Permeated with the rambunctious imagery of popular caricature, and Rowlandsonian satire, comic valentines were a wholly commercial invention. Little foundation existed in the folk traditions of St. Valentine’s Day for turning the holiday into a charivari, but that is where the market took it as merchants appropriated carnivalesque images of inversion, lewdness, and insult, effectively commodifying pranksterism and practical joking.” [2]

In both the United States and England, the market for comic valentines rivaled that for sentimental valentines, with their sales numbers about equal in the 1840s and 1850s. During the Civil War, American companies, even the serious Charles Magnus, took aim at those who dodged the draft on both sides of the conflict, making lighthearted fun of the serious situation. After the Civil War, there was a new kind of crude comic valentine on the market, sold for a penny, and provocative in hurtful ways: the “penny dreadful.” Men could be characterized by their political choices and their handicaps, or even their surprise upon returning home to find their wives with new babies. No subject was exempt.

In both the United States and England, the market for comic valentines rivaled that for sentimental valentines, with their sales numbers about equal in the 1840s and 1850s.

The McLoughlin Company, famous for quality chromolithograph books and toys, developed a form of comic valentine which became increasingly popular. These horrific messages might have been sent from one person or business associate to another as a joke, or possibly as an anonymous criticism of one’s appearance or occupation or dress. The sole artist of this genre was a gentleman named Charles J. Howard. Working in New York, he created caricatures that reflected every occupation, sports, personality, and type. In a special issue published on February 11, 1900, the New York World newspaper wrote about the McLoughlin company’s comic valentine business: “20,000,000 are Printed and Circulated Annually and One Firm in New York Makes Them All.” The valentines were described as “destroyers of self-conceit and complacency,” and Howard was pictured as “the guilty wretch” responsible for all of them. [3] In one interview, Howard apparently bemoaned the fact that his work had occasioned so much pain and sought to rectify that by writing sweet books for children using the alias Constance White. Nevertheless, these valentines, usually signed with a hasty capital H, are what most people think of today as Victorian valentines.

The actual paper, design, and penmanship of a valentine has always been an integral part of its enjoyment. Paper engineers created valentines where the recipient was forced to manipulate the paper to find the message. The tactile quality of maneuvering the paper that had been touched by the lover, with the actual “fingerprints of love,” made the valentine personal, private, and worth cherishing. In sentimental valentines, there might have been a romantic surprise, like a cobweb mechanism which would hide a loving image, or a secret message hidden beneath a flower petal; with comic valentines, that was not the case. The movable paper in a comic usually transformed the person. By simply lifting a flap of paper or moving a wheel, for example, a reader might turn a young woman into an old hag. Manufacturers created a mechanical curiosity, enabling the image to be transformed, as seen in the examples below.

|

|

Left: British, 19th century. Comic Valentine (funny man), ca. 1860. Hand colored lithograph, 8 1/2 × 5 1/2 in. (21.5 × 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.466). Right: British, 19th Century. Comic Valentine (shy woman), ca. 1860. Hand colored lithograph, 8 1/8 × 5 in. (20.5 × 12.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard Riddell, 1981 (1981.1136.467)

Yet one must wonder, who would send these—perhaps political enemies, or friends, or both? Generally unsigned, and at a penny, almost anyone could afford to partake in this anonymous anti-valentine experience. More expensive “comics,” which were engraved or lithographed on fine paper, were also available. They could poke malicious fun at society’s weaknesses and even reveal personal flaws within oneself. It seems that the later nineteenth-century valentines had adopted the ancient characteristics of critical satire and provided continuity from centuries earlier.

This year, 2024, is the quadrennial celebration of the leap year. Each fourth year, an extra day is added to our February calendar to keep it astronomically synchronized. Called a bissextile year, tradition has empowered women to take “ladies’ choice” in all matters of etiquette with the opposite sex, including proposals of marriage. As imagined, this provided great fodder for absurd or caustic comic valentines. One tradition was that if a man rejected a lady’s proposal, he was obliged to give her a silk dress, which included a red petticoat!

Considering human nature, it must be gratifying to today’s manufacturers that they still find a receptive and appreciative audience for contemporary versions of both the malignant and the purist valentines, on which the holiday was built. One must recall the sacred origins of the holiday, and its predominant message of love and sentimentality. Often used as a proclamation of love and a vehicle for a marriage proposal, the romantic missive outshines the comic varieties in artistry and sheer volume. Despite the large numbers of comic valentines that were sent, there was little to compare with the success of Cupid and his arrows.

Notes

[1] Sarah Scudgell Wilkinson (1779–1831): https://womensprinthistoryproject.com/person/471

[2] Leigh Eric Schmidt, “The Fashioning of a Modern Holiday: St. Valentine’s Day 1840–1870.” Winterthur Portfolio. Winter 1993, Volume 28, Number 4, pp. 209–254

[3] “‘Comic’ Valentines,” New York World. February 11, 1900.