Traveling Exhibitions

Traveling Exhibitions Traveling Works of Art

Traveling Works of Art Conservation Projects

Conservation Projects Excavations

Excavations Fellows

Fellows Exchanges & Collaborations

Exchanges & Collaborations Multiple Items

Multiple Items

The Met Around the World presents the Met’s work via the global scope of its collection and as it extends across the nation and the world through a variety of domestic and international initiatives and programs, including exhibitions, excavations, fellowships, professional exchanges, conservation projects, and traveling works of art.

The Met Around the World is designed and maintained by the Office of the Director.

Traveling

Exhibitions

The Met organizes large and small exhibitions that travel beyond the Museum's walls, extending our scholarship to institutions across the world. See our national and international traveling exhibition program from 2009 to the present.

Traveling

Works of Art

The Met lends works of art to exhibitions and institutions worldwide to expose its collection to the broadest possible audience. See our current national and international loans program.

Conservation

Projects

The preservation of works of art is a fundamental part of the Met's mission. Our work in this area includes treating works of art from other collections. See our national and international conservation activities from 2009 to the present.

Excavations

The Met has conducted excavations for over 100 years in direct partnership with source countries at some of the most important archaeological sites in the world. Today we continue this tradition in order to gain greater understanding of our ancient collections. See our national and international excavation program from the Met's founding to the present.

Fellows

The Met hosts students, scholars, and museum professionals so that they can learn from our staff and pursue independent research in the context of the Met's exceptional resources and facilities. See the activities of our current national and international fellows.

Exchanges & Collaborations

The Met's work takes many forms, from participation in exchange programs at partnering institutions and worldwide symposia to advising on a range of museum issues. These activities contribute to our commitment to advancing the work of the larger, global community of art museums. See our national and international exchange program and other collaborations from 2009 to the present.

The terraced temple of Hatshepsut (foreground) and the temple of Mentuhotep II at Deir el-Bahri (T 3120). Photograph by Harry Burton, ca. 1912. Archives of the Egyptian Expedition, Department of Egyptian Art.

The terraced temple of Hatshepsut (foreground) and the temple of Mentuhotep II at Deir el-Bahri (T 3120). Photograph by Harry Burton, ca. 1912. Archives of the Egyptian Expedition, Department of Egyptian Art. Work on granite statue fragments (M10C 58). Photograph by Harry Burton, February 15, 1929. Archives of the Egyptian Expedition, Department of Egyptian Art.

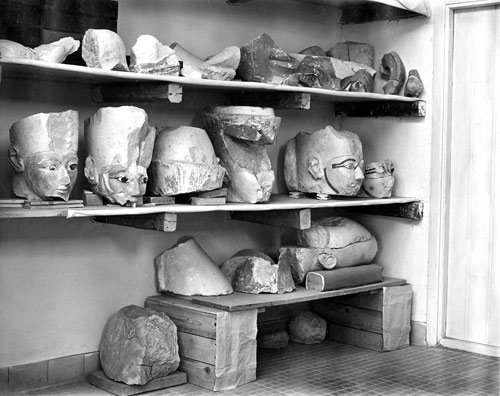

Work on granite statue fragments (M10C 58). Photograph by Harry Burton, February 15, 1929. Archives of the Egyptian Expedition, Department of Egyptian Art. Fragments of limestone architectural statues of Hatshepsut from the upper court (M9C 330). Photograph by Harry Burton, April 1928. Archives of the Egyptian Expedition, Department of Egyptian Art.

Fragments of limestone architectural statues of Hatshepsut from the upper court (M9C 330). Photograph by Harry Burton, April 1928. Archives of the Egyptian Expedition, Department of Egyptian Art. Fragments of a seated statue of Hatshepsut made of indurated limestone (29.3.2). Photograph by Harry Burton, 1929 (M10C 71). Archives of the Egyptian Expedition, Department of Egyptian Art.

Fragments of a seated statue of Hatshepsut made of indurated limestone (29.3.2). Photograph by Harry Burton, 1929 (M10C 71). Archives of the Egyptian Expedition, Department of Egyptian Art.

Statue of Hatshepsu, seated

New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, Joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, ca. 1473–1458 B.C.

Egypt, Upper Egypt; Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Hatshepsut Hole, Senenmut Quarry, MMA 1926–1928/Lepsius 1843–1845

Rogers Fund, 1929 (29.3.2)

Egypt

1923–1931

Hatshepsut was the most significant of Egypt's female rulers. She came to power early in Dynasty 18, at the beginning of the New Kingdom. First as regent, then as co-ruler with her stepson and nephew, Thutmose III, Hatshepsut wielded the authority of king for more than twenty years (ca. 1479–1458 B.C.).

The crowning architectural achievement of Hatshepsut's reign was her terraced funerary temple, Djeser-djeseru, at Deir el-Bahri in western Thebes opposite modern Luxor. The temple, with its three levels of pillared porticoes, combined building, sculpture, and landscape in one of the world's great architectural masterpieces. Djeser-djeseru was partly inspired by a neighboring temple built five centuries earlier for Mentuhotep II, founder of the Middle Kingdom. By associating herself with Mentuhotep, one of Egypt's greatest rulers, Hatshepsut reinforced her own position as king.

Hatshepsut revitalized the royal funerary complex by combining her mortuary cult with a temple of the gods. Chief among the deities worshipped at Djeser-djeseru was Amun, whose principal temple, Karnak, was at Thebes, on the east bank of the Nile. Amun's chapel dominates the central axis of Djeser-djeseru, and once a year, during the "Beautiful Feast of the Valley," the god's image was brought from Karnak, in a boat-shaped shrine, to rest in Hatshepsut's temple.

Although Djeser-djeseru was partly destroyed by falling rock from the cliffs above, it was never completely buried. In the seventh century A.D., a Coptic monastery of mudbrick was constructed on the ruins of the upper terrace and, centuries later, the ruined monastery inspired the name of the site, Deir el-Bahri (northern monastery).

Excavations

The temples of Hatshepsut and Mentuhotep II were well known when the Metropolitan Museum's excavators, led by Museum Egyptologist Herbert E. Winlock, began clearing the area in front of them in 1923. Winlock was searching for information about the early Middle Kingdom when he began finding fragments of statues belonging to the time of Hatshepsut. Some were pieces of limestone sculpture that had been part of the temple architecture. These giant images of Hatshepsut had once decorated the portico and niches of the upper terrace. Other fragments of granite and sandstone came from huge sphinxes and freestanding statues of Hatshepsut that had lined the processional way leading to the sanctuary of Amun. The sculpture had been destroyed some twenty years after Hatshepsut's death by her nephew, Thutmose III, for reasons that still are not completely understood.

Between 1923 and 1931, tens of thousands of fragments—some weighing more than a ton, others smaller than a human fist—were recovered and sorted. Examples of the architectural statues were reattached to the temple's facade and some of the sphinxes and other freestanding statues were reassembled and divided between the Egyptian Antiquities Service and the Metropolitan Museum. Objects acquired by the Museum in this division of finds are on view in Egyptian galleries 115, 116, and 117.